A foundation to healing and self-understanding

For those of us who have lived between cultures, the quiet act of naming our truth can be a radical reclamation.

On a picture-perfect weekend, I reconnected with my roots at the May 2025 Calabash International Literary Festival held at Treasure Beach on Jamaica’s south shore. Against a backdrop of crashing waves, I sat under a tent with more than a thousand attendees listening to established and upcoming writers read their works and share their wisdom.

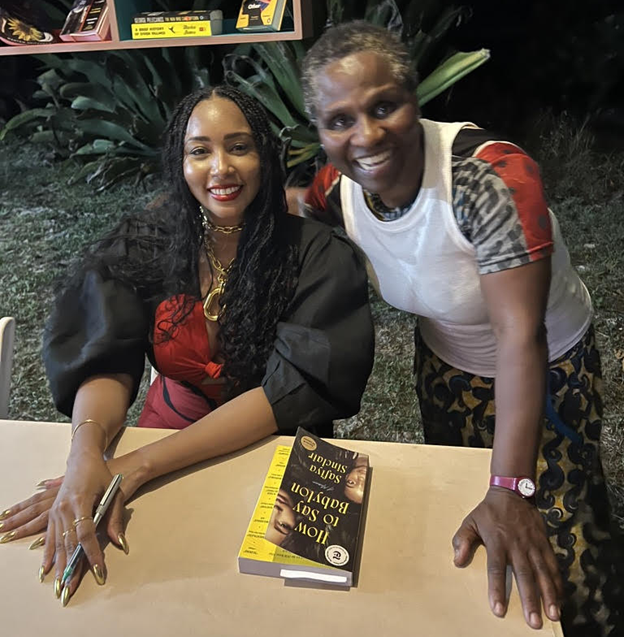

There, I also reconnected with my good friend, Andrea, and ate scrumptious fried breadfruit and coconut rundown – favorite foods from my childhood – and swayed to the rhythm of reggae and Afrobeat songs playing in the background. It was a weekend that reminded me of the ways our environment and community shape the stories we carry.

I thought about our Jamaican writer and poet, Safiya Sinclair, and her powerful reading of How to Say Babylon. Filled with Safiya’s experiences of a childhood spent along the north coast. Her mother focused on education and provided opportunities for Safiya and her siblings to quench their academic hunger. Safiya also documented life with a father who, steeped in his Rastafarian religion and culture, imposed rigid rules, demanding that his daughter adhere to modesty in dress and appearance, and demonstrate total obedience and submission, leading to many years of extreme social isolation for Safiya.

It was a stark and tender illustration of how naming our truth—even when it challenges those closest to us—can be a path to liberation.

My last day at the festival, I walked to the beach. Except for a couple performing yoga poses under a tree, a father and daughter duo, and I were the only other individuals on the beach at that early hour. Despite the meditative powers of the waves, I heeded my new friends’ warning and only ventured shoulder deep, mindful of the rough current that so quickly could have swept us far from the shore. In the quiet hush of the early morning, I felt the tension between danger and possibility—between naming our fears and still daring to show up.

As I listened to the crashing of waves, I wondered about how many of us grew up in environments where our reality was denied or minimized – where we heard “I’ll give you something to cry about” or “it wasn’t that bad.” “Don’t be so sensitive.” I know that these subtle (and not-so-subtle) invalidations led us to doubt our perceptions, mistrust our emotions, and ultimately disconnect from our own experiences and reality, which, even as we succeeded academically and professionally, at times, resulted in feelings of depression and anxiety.

We become estranged from ourselves when we are told, again and again, that our truth doesn’t matter.

It’s no wonder that we find ourselves questioning our worth, our memories, and our ability to feel safe in the world.

I also know that when we dare to name our experiences, what we see and feel, we reclaim our power. We locate ourselves in truth and take a step towards feeling better. I thought about Safiya’s memoir and her courage in naming what she felt, saw, experienced, and observed in her household and community, and the transformative impact her documenting had on her family relationships. “My father is in the audience,” a beaming, emotional, and proud Safiya said that Friday night at the end of her talk at Calabash.

In those few words, she named both the rupture and the bridge—showing us that even the most painful truths can lead to a kind of healing.

Practicing self-awareness is one step towards naming our reality.

Notice and practice non-judgmental observation:

- How do you feel? Sad? Happy? Disappointed? Angry?

- What sensations do you observe throughout your body; in your chest? shoulders? stomach? Legs?

- How is your breathing? Smooth? Shallow?

Sometimes we hesitate to name our feelings because we fear that naming them will make them bigger. But the opposite is true: Naming is how we face what seems overwhelming.

Language is a powerful regulator. Naming what is happening internally or externally helps to clarify our reality and anchor us in the present.

Labeling an experience can reduce its intensity. For example:

“I’m feeling overwhelmed.”

“I feel anxious when I walk into this room.”

“I feel my shoulders tensing during a conversation.”

These are not just words; they are lifelines. They offer us a sense of control and connection to ourselves.

In observing body sensations, feelings, and images, we are practicing presence and self-awareness and are creating a vocabulary for our inner world. In doing so, we are also creating space for change.

Writing our observations, daily journaling also helps to clarify them. Writing can:

- Affirm that our experience is real and worthy of attention;

- Slow down automatic responses and invite conscious awareness;

- Regulate our nervous system.

Naming isn’t always easy. It can stir up discomfort, anger, fear, or even grief. Naming our experiences – particularly if we grew up in a household where such actions were discouraged – is an act of courage, can potentially move us toward integration, self-compassion, and wholeness.

Each time we name what’s true for us, we interrupt the cycle of silence. We give our inner lives the dignity they deserve.

The words we use to describe our inner life are not indulgent or excessive. They are essential. They are the bridge between silence and understanding, disconnection and belonging.

So, here’s the question I invite you to carry forward: What might change if you could say, “this is my truth”—and trust that it matters?

If you’re feeling the weight of this question, or you’re unsure how to navigate the space that opens up when you answer it, I’d be honored to hold a 15-minute conversation with you to help you find clarity and next steps.